4. What Are The Main Characteristics Of Animals That Belong To The Phylum Nematoda?

| Nematode Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

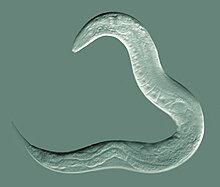

| Caenorhabditis elegans, a model species of roundworm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa |

| Clade: | Nematoida |

| Phylum: | Nematoda Diesing, 1861 |

| Classes | |

(see text) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The nematodes ( NEM-ə-tohdz or [2] NEEM- Greek: Νηματώδη ; Latin: Nematoda) or roundworms plant the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes),[3] [4] with institute-parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms.[5] They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a broad range of environments. Taxonomically, they are classified along with insects and other moulting animals in the clade Ecdysozoa, and unlike flatworms, accept tubular digestive systems with openings at both ends. Like tardigrades, they have a reduced number of Hox genes, but their sister phylum Nematomorpha has kept the ancestral protostome Hox genotype, which shows that the reduction has occurred within the nematode phylum.[6]

Nematode species can exist difficult to distinguish from 1 some other. Consequently, estimates of the number of nematode species described to date vary by author and may change chop-chop over time. A 2013 survey of brute biodiversity published in the mega periodical Zootaxa puts this figure at over 25,000.[7] [eight] Estimates of the total number of extant species are subject to fifty-fifty greater variation. A widely referenced[9] article published in 1993 estimated there may be over 1 million species of nematode.[10] A subsequent publication challenged this claim, estimating the figure to be at least xl,000 species.[11] Although the highest estimates (up to 100 1000000 species) have since been deprecated, estimates supported by rarefaction curves,[12] [13] together with the employ of Dna barcoding[14] and the increasing acknowledgment of widespread cryptic species among nematodes,[15] take placed the figure closer to 1 one thousand thousand species.[sixteen]

Nematodes accept successfully adjusted to nearly every ecosystem: from marine (salt) to fresh water, soils, from the polar regions to the torrid zone, as well equally the highest to the lowest of elevations (including mountains). They are ubiquitous in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial environments, where they often outnumber other animals in both individual and species counts, and are plant in locations as diverse equally mountains, deserts, and oceanic trenches. They are found in every part of the earth's lithosphere,[17] even at keen depths, 0.9–3.6 km (iii,000–12,000 ft) below the surface of the Earth in aureate mines in South Africa.[eighteen] [19] [xx] [21] [22] They represent xc% of all animals on the ocean floor.[23] In total, 4.4 × 1020 nematodes inhabit the World'southward topsoil, or approximately threescore billion for each homo, with the highest densities observed in tundra and boreal forests.[24] Their numerical say-so, often exceeding a million individuals per foursquare meter and accounting for most lxxx% of all private animals on globe, their diversity of lifecycles, and their presence at diverse trophic levels signal to an of import role in many ecosystems.[24] [25] They accept been shown to play crucial roles in polar ecosystems.[26] [27] The roughly 2,271 genera are placed in 256 families.[28] The many parasitic forms include pathogens in nigh plants and animals. A third of the genera occur as parasites of vertebrates; near 35 nematode species occur in humans.[28]

Nathan Cobb, a nematologist, described the ubiquity of nematodes on Earth thus:

In curt, if all the matter in the universe except the nematodes were swept away, our world would still be dimly recognizable, and if, as disembodied spirits, we could then investigate information technology, we should find its mountains, hills, vales, rivers, lakes, and oceans represented by a picture of nematodes. The location of towns would exist decipherable since, for every massing of human beings, at that place would be a respective massing of certain nematodes. Copse would withal stand in ghostly rows representing our streets and highways. The location of the diverse plants and animals would still be decipherable, and, had we sufficient knowledge, in many cases even their species could be determined past an examination of their quondam nematode parasites.[29]

Etymology [edit]

The give-and-take nematode comes from the Modern Latin compound of nemat- "thread" (from Greek nema, genitive nematos "thread," from stem of nein "to spin"; encounter needle) + -odes "similar, of the nature of" (see -oid).

Taxonomy and systematics [edit]

Eophasma jurasicum, a fossilized nematode

Spiruridae Dirofilaria immitis

History [edit]

In 1758, Linnaeus described some nematode genera (east.chiliad., Ascaris), and then included in the Vermes.

The name of the group Nematoda, informally called "nematodes", came from Nematoidea, originally defined by Karl Rudolphi (1808),[30] from Aboriginal Greek νῆμα (nêma, nêmatos, 'thread') and -eiδἠς (-eidēs, 'species'). It was treated as family Nematodes by Burmeister (1837).[30]

At its origin, the "Nematoidea" erroneously included Nematodes and Nematomorpha, attributed past von Siebold (1843). Along with Acanthocephala, Trematoda, and Cestoidea, it formed the obsolete group Entozoa,[31] created by Rudolphi (1808).[32] They were as well classed along with Acanthocephala in the obsolete phylum Nemathelminthes by Gegenbaur (1859).

In 1861, M. M. Diesing treated the group as gild Nematoda.[thirty] In 1877, the taxon Nematoidea, including the family unit Gordiidae (horsehair worms), was promoted to the rank of phylum past Ray Lankester. The first clear distinction between the nemas and gordiids was realized by Vejdovsky when he named a group to comprise the horsehair worms the guild Nematomorpha. In 1919, Nathan Cobb proposed that nematodes should be recognized solitary as a phylum.[33] He argued they should exist called "nema" in English language rather than "nematodes" and defined the taxon Nemates (later emended equally Nemata, Latin plural of nema), listing Nematoidea sensu restricto as a synonym.

Still, in 1910, Grobben proposed the phylum Aschelminthes and the nematodes were included in every bit course Nematoda along with class Rotifera, form Gastrotricha, grade Kinorhyncha, class Priapulida, and class Nematomorpha (The phylum was subsequently revived and modified by Libbie Henrietta Hyman in 1951 every bit Pseudoceolomata, simply remained like). In 1932, Potts elevated the class Nematoda to the level of phylum, leaving the name the aforementioned. Despite Potts' classification being equivalent to Cobbs', both names have been used (and are still used today) and Nematode became a popular term in zoological science.[34]

Since Cobb was the first to include nematodes in a detail phylum separated from Nematomorpha, some researchers consider the valid taxon proper noun to be Nemates or Nemata, rather than Nematoda,[35] because of the zoological dominion that gives priority to the first used term in case of synonyms.

Phylogeny [edit]

The phylogenetic relationships of the nematodes and their close relatives among the protostomian Metazoa are unresolved. Traditionally, they were held to be a lineage of their own, but in the 1990s, they were proposed to form the group Ecdysozoa together with moulting animals, such as arthropods. The identity of the closest living relatives of the Nematoda has e'er been considered to be well resolved. Morphological characters and molecular phylogenies agree with placement of the roundworms as a sis taxon to the parasitic Nematomorpha; together, they make up the Nematoida. Along with the Scalidophora (formerly Cephalorhyncha), the Nematoida form the clade Cycloneuralia, but much disagreement occurs both between and amongst the available morphological and molecular data. The Cycloneuralia or the Introverta—depending on the validity of the former—are often ranked as a superphylum.[36]

Nematode systematics [edit]

Due to the lack of knowledge regarding many nematodes, their systematics is contentious. An early and influential classification was proposed by Chitwood and Chitwood[37]—later revised by Chitwood[38]—who divided the phylum into ii classes—Aphasmidia and Phasmidia. These were later renamed Adenophorea (gland bearers) and Secernentea (secretors), respectively.[39] The Secernentea share several characteristics, including the presence of phasmids, a pair of sensory organs located in the lateral posterior region, and this was used as the basis for this division. This scheme was adhered to in many after classifications, though the Adenophorea were not in a uniform group.

Initial studies of incomplete Deoxyribonucleic acid sequences[40] suggested the being of five clades:[41]

- Dorylaimida

- Enoplia

- Spirurina

- Tylenchina

- Rhabditina

The Secernentea seem to be a natural group of close relatives, while the "Adenophorea" appear to be a paraphyletic assemblage of roundworms that retain a good number of ancestral traits. The old Enoplia practice not seem to be monophyletic, either, simply do contain two distinct lineages. The old group "Chromadoria" seems to be some other paraphyletic assemblage, with the Monhysterida representing a very aboriginal pocket-sized group of nematodes. Among the Secernentea, the Diplogasteria may need to be united with the Rhabditia, while the Tylenchia might be paraphyletic with the Rhabditia.[42]

The agreement of roundworm systematics and phylogeny as of 2002 is summarised below:

Phylum Nematoda

- Basal social club Monhysterida

- Grade Dorylaimida

- Course Enoplea

- Class Secernentea

- Subclass Diplogasteria (disputed)

- Bracket Rhabditia (paraphyletic?)

- Subclass Spiruria

- Subclass Tylenchia (disputed)

- "Chromadorea" aggregation

Subsequently work has suggested the presence of 12 clades.[43] The Secernentea—a grouping that includes virtually all major animal and constitute 'nematode' parasites—plain arose from within the Adenophorea.

In 2019, a study identified one conserved signature indel (CSI) found exclusively in members of the phylum Nematoda through comparative genetic analyses.[44] The CSI consists of a unmarried amino acid insertion inside a conserved region of a Na(+)/H(+) commutation regulatory factor protein NRFL-i and is a molecular marking that distinguishes the phylum from other species.[44]

A major effort past a collaborative wiki called 959 Nematode Genomes is underway to improve the systematics of this phylum.[45]

An analysis of the mitochondrial Dna suggests that the following groupings are valid[46]

- subclass Dorylaimia

- orders Rhabditida, Trichinellida and Mermithida

- suborder Rhabditina

- infraorders Spiruromorpha and Oxyuridomorpha

In 2022 a new nomenclature of the entire phylum Nematoda was presented past M. Hodda. Information technology was based on current molecular, developmental and morphological bear witness.[47]

Anatomy [edit]

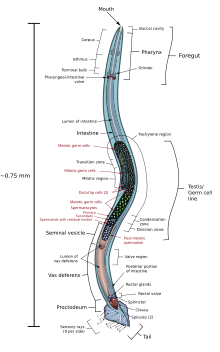

Internal anatomy of a male person C. elegans nematode

Nematodes are very pocket-sized, slender worms: typically about 5 to 100 µm thick, and 0.1 to ii.five mm long.[48] The smallest nematodes are microscopic, while free-living species can reach as much as five cm (two in), and some parasitic species are larger still, reaching over 1 1000 (3 ft) in length.[49] : 271 The body is often ornamented with ridges, rings, bristles, or other distinctive structures.[50]

The head of a nematode is relatively distinct. Whereas the remainder of the torso is bilaterally symmetrical, the caput is radially symmetrical, with sensory beard and, in many cases, solid 'caput-shields' radiating outwards around the rima oris. The mouth has either three or six lips, which often bear a series of teeth on their inner edges. An adhesive 'caudal gland' is often found at the tip of the tail.[51]

The epidermis is either a syncytium or a unmarried layer of cells, and is covered past a thick collagenous cuticle. The cuticle is often of a circuitous structure and may take two or three singled-out layers. Underneath the epidermis lies a layer of longitudinal musculus cells. The relatively rigid cuticle works with the muscles to create a hydroskeleton, as nematodes lack circumferential muscles. Projections run from the inner surface of musculus cells towards the nervus cords; this is a unique organisation in the creature kingdom, in which nervus cells normally extend fibers into the muscles rather than vice versa.[51]

Digestive system [edit]

The oral crenel is lined with cuticle, which is often strengthened with structures, such equally ridges, particularly in carnivorous species, which may deport a number of teeth. The oral fissure oftentimes includes a sharp stylet, which the animal can thrust into its prey. In some species, the stylet is hollow and can exist used to suck liquids from plants or animals.[51]

The mouth opens into a muscular, sucking pharynx, also lined with cuticle. Digestive glands are establish in this region of the gut, producing enzymes that get-go to break down the food. In stylet-bearing species, these may even exist injected into the casualty.[51]

No stomach is present, with the pharynx connecting directly to a muscleless intestine that forms the main length of the gut. This produces further enzymes, and also absorbs nutrients through its single-jail cell-thick lining. The last portion of the intestine is lined past cuticle, forming a rectum, which expels waste matter through the anus just beneath and in front end of the tip of the tail. The movement of food through the digestive system is the result of the body movements of the worm. The intestine has valves or sphincters at either cease to help control the movement of food through the body.[51]

Excretory organisation [edit]

Nitrogenous waste is excreted in the class of ammonia through the body wall, and is not associated with any specific organs. Nevertheless, the structures for excreting salt to maintain osmoregulation are typically more complex.[51]

In many marine nematodes, one or two unicellular 'renette glands' excrete salt through a pore on the underside of the creature, shut to the pharynx. In well-nigh other nematodes, these specialized cells take been replaced by an organ consisting of two parallel ducts connected past a single transverse duct. This transverse duct opens into a common canal that runs to the excretory pore.[51]

Nervous system [edit]

Four peripheral nerves run along the length of the body on the dorsal, ventral, and lateral surfaces. Each nerve lies within a string of connective tissue lying beneath the cuticle and between the muscle cells. The ventral nerve is the largest, and has a double construction frontward of the excretory pore. The dorsal nervus is responsible for motor control, while the lateral nerves are sensory, and the ventral combines both functions.[51]

The nervous system is besides the only identify in the nematode body that contains cilia, which are all nonmotile and with a sensory role.[52] [53]

At the inductive cease of the animal, the nerves branch from a dense, circular nervus (nervus ring) round surrounding the pharynx, and serving as the brain. Smaller nerves run frontwards from the band to supply the sensory organs of the head.[51]

The bodies of nematodes are covered in numerous sensory beard and papillae that together provide a sense of touch. Behind the sensory bristles on the caput lie 2 minor pits, or 'amphids'. These are well supplied with nerve cells and are probably chemoreception organs. A few aquatic nematodes possess what announced to be pigmented eye-spots, but whether or non these are actually sensory in nature is unclear.[51]

Reproduction [edit]

Extremity of a male nematode showing the spicule, used for copulation, bar = 100 µm[54]

Most nematode species are dioecious, with split up male person and female individuals, though some, such as Caenorhabditis elegans, are androdioecious, consisting of hermaphrodites and rare males. Both sexes possess one or two tubular gonads. In males, the sperm are produced at the end of the gonad and drift along its length equally they mature. The testis opens into a relatively wide seminal vesicle and and then during intercourse into a glandular and muscular ejaculatory duct associated with the vas deferens and cloaca. In females, the ovaries each open up into an oviduct (in hermaphrodites, the eggs enter a spermatheca get-go) and and then a glandular uterus. The uteri both open into a common vulva/vagina, normally located in the middle of the morphologically ventral surface.[51]

Reproduction is usually sexual, though hermaphrodites are capable of cocky-fertilization. Males are usually smaller than females or hermaphrodites (ofttimes much smaller) and often have a characteristically bent or fan-shaped tail. During copulation, i or more chitinized spicules move out of the cloaca and are inserted into the genital pore of the female. Amoeboid sperm clamber along the spicule into the female person worm. Nematode sperm is idea to exist the only eukaryotic cell without the globular protein G-actin.

Eggs may be embryonated or unembryonated when passed by the female person, meaning their fertilized eggs may not even so be developed. A few species are known to exist ovoviviparous. The eggs are protected by an outer beat out, secreted past the uterus. In free-living roundworms, the eggs hatch into larvae, which appear essentially identical to the adults, except for an underdeveloped reproductive organisation; in parasitic roundworms, the lifecycle is often much more complicated.[51]

Nematodes as a whole possess a wide range of modes of reproduction.[55] Some nematodes, such every bit Heterorhabditis spp., undergo a process called endotokia matricida: intrauterine birth causing maternal death.[56] Some nematodes are hermaphroditic, and keep their self-fertilized eggs inside the uterus until they hatch. The juvenile nematodes then ingest the parent nematode. This procedure is significantly promoted in environments with a depression nutrient supply.[56]

The nematode model species C. elegans, C. briggsae, and Pristionchus pacificus, among other species, exhibit androdioecy,[57] which is otherwise very rare amongst animals. The single genus Meloidogyne (root-knot nematodes) exhibits a range of reproductive modes, including sexual reproduction, facultative sexuality (in which most, only not all, generations reproduce asexually), and both meiotic and mitotic parthenogenesis.

The genus Mesorhabditis exhibits an unusual form of parthenogenesis, in which sperm-producing males copulate with females, but the sperm do not fuse with the ovum. Contact with the sperm is essential for the ovum to brainstorm dividing, but because no fusion of the cells occurs, the male person contributes no genetic material to the offspring, which are essentially clones of the female.[51]

Free-living species [edit]

Different free-living species feed on materials every bit varied equally bacteria, algae, fungi, pocket-sized animals, fecal affair, dead organisms, and living tissues. Free-living marine nematodes are important and arable members of the meiobenthos. They play an important role in the decomposition process, aid in recycling of nutrients in marine environments, and are sensitive to changes in the environment acquired by pollution. One roundworm of annotation, C. elegans, lives in the soil and has found much utilise as a model organism. C. elegans has had its unabridged genome sequenced, the developmental fate of every cell determined, and every neuron mapped.

Parasitic species [edit]

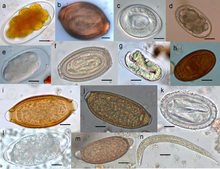

Eggs (more often than not nematodes) from stools of wild primates

Nematodes that commonly parasitise humans include ascarids (Ascaris), filarias, hookworms, pinworms (Enterobius), and whipworms (Trichuris trichiura). The species Trichinella spiralis, commonly known as the 'trichina worm', occurs in rats, pigs, bears, and humans, and is responsible for the affliction trichinosis. Baylisascaris usually infests wild animals, but can exist deadly to humans, as well. Dirofilaria immitis is known for causing heartworm affliction by inhabiting the hearts, arteries, and lungs of dogs and some cats. Haemonchus contortus is i of the most abundant infectious agents in sheep around the earth, causing great economic damage to sheep. In contrast, entomopathogenic nematodes parasitize insects and are more often than not considered beneficial by humans, but some attack beneficial insects.

One form of nematode is entirely dependent upon fig wasps, which are the sole source of fig fertilization. They prey upon the wasps, riding them from the ripe fig of the wasp'southward nascency to the fig flower of its death, where they kill the wasp, and their offspring await the birth of the next generation of wasps every bit the fig ripens.

A newly discovered parasitic tetradonematid nematode, Myrmeconema neotropicum, obviously induces fruit mimicry in the tropical emmet Cephalotes atratus. Infected ants develop brilliant reddish gasters (abdomens), tend to be more sluggish, and walk with their gasters in a conspicuous elevated position. These changes probable cause frugivorous birds to misfile the infected ants for berries, and swallow them. Parasite eggs passed in the bird's feces are subsequently collected by foraging C. atratus and are fed to their larvae, thus completing the lifecycle of M. neotropicum.[58]

Similarly, multiple varieties of nematodes have been found in the abdominal cavities of the primitively social sweat bee, Lasioglossum zephyrus. Within the female torso, the nematode hinders ovarian development and renders the bee less agile, thus less effective in pollen drove.[59]

Agriculture and horticulture [edit]

Depending on its species, a nematode may exist beneficial or detrimental to plant health. From agronomical and horticulture perspectives, the two categories of nematodes are the predatory ones, which impale garden pests such as cutworms and corn earworm moths, and the pest nematodes, such as the root-knot nematode, which set on plants, and those that act as vectors spreading found viruses betwixt crop plants.[60] Plant-parasitic nematodes include several groups causing severe ingather losses, taking 10% of crops worldwide every year.[61] The most mutual genera are Aphelenchoides (foliar nematodes), Ditylenchus, Globodera (white potato cyst nematodes), Heterodera (soybean cyst nematodes), Longidorus, Meloidogyne (root-knot nematodes), Nacobbus, Pratylenchus (lesion nematodes), Trichodorus, and Xiphinema (dagger nematodes). Several phytoparasitic nematode species crusade histological damages to roots, including the formation of visible galls (e.m. by root-knot nematodes), which are useful characters for their diagnostic in the field. Some nematode species transmit plant viruses through their feeding activity on roots. I of them is Xiphinema alphabetize, vector of grapevine fanleaf virus, an of import disease of grapes, some other ane is Xiphinema diversicaudatum, vector of arabis mosaic virus. Other nematodes attack bark and forest copse. The nigh of import representative of this grouping is Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, the pine woods nematode, nowadays in Asia and America and recently discovered in Europe.

Greenhouse growers use beneficial nematodes to control fungus gnats, the nematodes enter the larva of the gnats by way of their anus, mouth, and spiracles (breathing pores) and then release a bacteria which kills the gnat larvae; commonly used nematode species to control pests on greenhouse crops include Steinernema feltiae for fungus gnats and western flower thrips, Steinernema carpocapsae used to control shore flies, Steinernema kraussei for control of blackness vine weevils, and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora to control protrude larvae.[62]

Rotations of plants with nematode-resistant species or varieties is one ways of managing parasitic nematode infestations. For example, marigolds, grown over one or more seasons (the effect is cumulative), tin can be used to command nematodes.[63] Some other is handling with natural antagonists such as the fungus Gliocladium roseum. Chitosan, a natural biocontrol, elicits establish defence force responses to destroy parasitic cyst nematodes on roots of soybean, corn, sugar beet, murphy, and tomato crops without harming beneficial nematodes in the soil.[64] Soil steaming is an efficient method to kill nematodes before planting a ingather, only indiscriminately eliminates both harmful and beneficial soil creature.

The golden nematode Globodera rostochiensis is a particularly harmful multifariousness of nematode pest that has resulted in quarantines and ingather failures worldwide. CSIRO has found a 13- to 14-fold reduction of nematode population densities in plots having Indian mustard Brassica juncea light-green manure or seed meal in the soil.[65]

Epidemiology [edit]

Disability-adjusted life year for intestinal nematode infections per 100,000 in 2002.

< 25

25–fifty

50–75

75–100

100–120

120–140

140–160

160–180

180–200

200–220

220–240

> 240

no data

A number of intestinal nematodes cause diseases affecting human beings, including ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm disease. Filarial nematodes crusade filariases. Furthermore, studies have shown that parasitic nematodes infect American eels causing harm to the eel's swim bladder,[66] dairy animals like cattle and buffalo,[67] and all species of sheep.[68]

Soil ecosystems [edit]

Almost 90% of nematodes reside in the top fifteen cm (6") of soil. Nematodes do not decompose organic matter, but, instead, are parasitic and gratis-living organisms that feed on living material. Nematodes can effectively regulate bacterial population and customs composition—they may eat up to 5,000 bacteria per minute. Also, nematodes tin play an of import office in the nitrogen cycle past style of nitrogen mineralization.[48]

One grouping of carnivorous fungi, the nematophagous fungi, are predators of soil nematodes.[69] They set enticements for the nematodes in the form of lassos or adhesive structures.[lxx] [71] [72]

Survivability [edit]

Nematode worms (C. elegans), part of an ongoing inquiry project conducted on the 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia mission STS-107, survived the re-entry breakup. Information technology is believed to be the first known life form to survive a near unprotected atmospheric descent to Earth'due south surface.[73] [74] In a research projection published in 2012, it was found that the Antarctic Nematodes (P. davidi) was able to withstand intracellular freezing depending on how well it was fed. When compared between fed and starved nematodes, the survival rate increased in the fed group and decreased in the starved group.[75]

See too [edit]

- Biological pest control – Controlling pests using other organisms

- Capillaria – Genus of roundworms

- List of organic gardening and farming topics

- List of parasites of humans

- Toxocariasis – Disease of humans caused by larvae of the dog, the true cat or the trick roundworm: A helminth infection of humans caused by the domestic dog or cat roundworm, Toxocara canis or Toxocara cati

- Worm bagging – Process where nematode larvae hatch within, consume, and emerge from the parent

References [edit]

- ^ "Nematode Fossils—Nematoda". The Virtual Fossil Museum.

- ^ bkhb. [mhmg mhmg]. ;

- ^ "Nomenclature of Brute Parasites". Archived from the original on 2017-10-06. Retrieved 2016-02-25 .

- ^ Garcia, Lynne (29 October 1999). "Classification of Human being Parasites, Vectors, and Similar Organisms". Clinical Infectious Diseases. Los Angeles, California: Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, UCLA Medical Center. 29 (four): 734–6. doi:x.1086/520425. PMID 10589879.

- ^ Hay, Frank. "Nematodes - the good, the bad and the ugly". APS News & Views. American Phytopathological Society. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Baker, Emily A.; Woollard, Alison (2019). "How Weird is the Worm? Evolution of the Developmental Cistron Toolkit in Caenorhabditis elegans". Periodical of Developmental Biology. seven (iv): nineteen. doi:ten.3390/jdb7040019. PMC6956190. PMID 31569401.

- ^ Hodda, K (2011). "Phylum Nematoda Cobb, 1932. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness". Zootaxa. 3148: 63–95. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.xi.

- ^ Zhang, Z (2013). "Fauna biodiversity: An update of classification and diverseness in 2013. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013)". Zootaxa. 3703 (ane): 5–11. doi:x.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.iii.

- ^ "Contempo developments in marine benthic biodiversity research". ResearchGate . Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Lambshead, PJD (1993). "Recent developments in marine benthic biodiversity enquiry". Oceanis. 19 (6): 5–24.

- ^ Anderson, Roy C. (eight February 2000). Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission. CABI. pp. 1–2. ISBN9780851994215.

Estimates of 500,000 to a million species have no ground in fact.

- ^ Lambshead PJ, Boucher Chiliad (2003). "Marine nematode abyssal biodiversity—hyperdiverse or hype?". Journal of Biogeography. 30 (iv): 475–485. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00843.10.

- ^ Qing X, Bert Due west (2019). "Family Tylenchidae (Nematoda): an overview and perspectives". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. xix (3): 391–408. doi:ten.1007/s13127-019-00404-iv. S2CID 190873905.

- ^ Floyd R, Abebe E, Papert A, Blaxter Chiliad (2002). "Molecular barcodes for soil nematode identification". Molecular Ecology. 11 (4): 839–850. doi:ten.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01485.ten. PMID 11972769. S2CID 12955921.

- ^ Derycke Southward, Sheibani Tezerji R, Rigaux A, Moens T (2012). "Investigating the ecology and development of cryptic marine nematode species through quantitative real-fourth dimension PCR of the ribosomal ITS region". Molecular Ecology Resources. 12 (4): 607–619. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0998.2012.03128.x. hdl:1854/LU-3127487. PMID 22385909. S2CID 4818657.

- ^ Blaxter, Mark (2016). "Imagining Sisyphus happy: DNA barcoding and the unnamed majority". Philosophical Transactions of the Imperial Lodge of London B. 371 (1702): 20150329. doi:x.1098/rstb.2015.0329. PMC4971181. PMID 27481781.

- ^ Borgonie G, García-Moyano A, Litthauer D, Bert Westward, Bester A, van Heerden E, Möller C, Erasmus M, Onstott TC (June 2011). "Nematoda from the terrestrial deep subsurface of S Africa". Nature. 474 (7349): 79–82. Bibcode:2011Natur.474...79B. doi:10.1038/nature09974. hdl:1854/LU-1269676. PMID 21637257. S2CID 4399763.

- ^ Lemonick MD (8 June 2011). "Could 'worms from Hell' mean there'due south life in space?". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ Bhanoo SN (1 June 2011). "Nematode constitute in mine is get-go subsurface multicellular organism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved thirteen June 2011.

- ^ "Gold mine". Nature. 474 (7349): 6. June 2011. doi:10.1038/474006b. PMID 21637213.

- ^ Drake Northward (one June 2011). "Subterranean worms from hell: Nature News". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2011.342. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ^ Borgonie 1000, García-Moyano A, Litthauer D, Bert Due west, Bester A, van Heerden E, Möller C, Erasmus K, Onstott TC (2 June 2011). "Nematoda from the terrestrial deep subsurface of South Africa". Nature. 474 (7349): 79–82. Bibcode:2011Natur.474...79B. doi:10.1038/nature09974. hdl:1854/LU-1269676. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 21637257. S2CID 4399763.

- ^ Danovaro R, Gambi C, Dell'Anno A, Corinaldesi C, Fraschetti S, Vanreusel A, Vincx Yard, Gooday AJ (January 2008). "Exponential decline of deep-sea ecosystem functioning linked to benthic biodiversity loss". Curr. Biol. 18 (1): i–8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.056. PMID 18164201. S2CID 15272791.

- "Deep-body of water species' loss could lead to oceans' collapse, report suggests". EurekAlert! (Press release). 27 December 2007.

- ^ a b van den Hoogen, Johan; Geisen, Stefan; Routh, Devin; Ferris, Howard; Traunspurger, Walter; Wardle, David A.; de Goede, Ron 1000. Thou.; Adams, Byron J.; Ahmad, Wasim (2019-07-24). "Soil nematode affluence and functional group composition at a global scale". Nature. 572 (7768): 194–198. Bibcode:2019Natur.572..194V. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1418-six. hdl:xx.500.11755/c8c7bc6a-585c-4a13-9e36-4851939c1b10. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 31341281. S2CID 198492891. Archived from the original on 2020-03-02. Retrieved 2019-12-10 .

- ^ Platt HM (1994). "foreword". In Lorenzen Southward, Lorenzen SA (eds.). The phylogenetic systematics of freeliving nematodes. London, UK: The Ray Club. ISBN978-0-903874-22-ix.

- ^ Cary, S. Craig; Green, T. 1000. Allan; Storey, Bryan C.; Sparrow, Ashley D.; Hogg, Ian D.; Katurji, Marwan; Zawar-Reza, Peyman; Jones, Irfon; Stichbury, Glen A. (2019-02-15). "Biotic interactions are an unexpected yet critical control on the complexity of an abiotically driven polar ecosystem". Communications Biological science. 2 (1): 62. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0274-5. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC6377621. PMID 30793041.

- ^ Adams, Byron J.; Wall, Diana H.; Storey, Bryan C.; Green, T. G. Allan; Barrett, John E.; S. Craig Cary; Hopkins, David West.; Lee, Charles K.; Bottos, Eric M. (2019-02-xv). "Nematodes in a polar desert reveal the relative role of biotic interactions in the coexistence of soil animals". Communications Biology. ii (i): 63. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0260-y. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC6377602. PMID 30793042.

- ^ a b Roy C. Anderson (eight February 2000). Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their development and transmission. CABI. p. i. ISBN978-0-85199-786-five.

- ^ Cobb, Nathan (1914). "Nematodes and their relationships". Yearbook. United States Department of Agriculture. pp. 472, 457–490. Archived from the original on ix June 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

Quote on p. 472.

- ^ a b c Chitwood BG (1957). "The English discussion "Nema" revised". Systematic Biology. 4 (45): 1619. doi:10.2307/sysbio/half dozen.4.184.

- ^ Siddiqi MR (2000). Tylenchida: parasites of plants and insects. Wallingford, Oxon, Uk: CABI Pub. ISBN978-0-85199-202-0.

- ^ Schmidt-Rhaesa A (2014). "Gastrotricha, Cycloneuralia and Gnathifera: General History and Phylogeny". In Schmidt-Rhaesa A (ed.). Handbook of Zoology (founded past Westward. Kükenthal). Vol. 1, Nematomorpha, Priapulida, Kinorhyncha, Loricifera. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter.

- ^ Cobb NA (1919). "The orders and classes of nemas". Contrib. Sci. Nematol. eight: 213–216.

- ^ Wilson, E. O. "Phylum Nemata". Plant and insect parasitic nematodes. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ "ITIS report: Nematoda". Itis.gov. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ "Bilateria". Tree of Life Web Project. Tree of Life Web Project. 2002. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Chitwood BG, Chitwood MB (1933). "The characters of a protonematode". J Parasitol. 20: 130.

- ^ Chitwood BG (1937). "A revised nomenclature of the Nematoda". Papers on Helminthology published in commemoration of the 30 year Jubileum of ... Thousand.J. Skrjabin ... Moscow: All-Union Lenin Academy of Agronomical Sciences. pp. 67–79.

- ^ Chitwood BG (1958). "The designation of official names for higher taxa of invertebrates". Balderdash Zool Nomencl. 15: 860–895. doi:10.5962/bhl.role.19410.

- ^ Coghlan, A. (7 Sep 2005). "Nematode genome evolution" (PDF). WormBook: 1–15. doi:x.1895/wormbook.one.fifteen.1. PMC4781476. PMID 18050393. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ Blaxter ML, De Ley P, Garey JR, Liu Lx, Scheldeman P, Vierstraete A, Vanfleteren JR, Mackey LY, Dorris M, Frisse LM, Vida JT, Thomas WK (March 1998). "A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda". Nature. 392 (6671): 71–75. Bibcode:1998Natur.392...71B. doi:10.1038/32160. PMID 9510248. S2CID 4301939.

- ^ "Nematoda". Tree of Life Web Project. Tree of Life Web Project. 2002. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Holterman M, van der Wurff A, van den Elsen Due south, van Megen H, Bongers T, Holovachov O, Bakker J, Helder J (2006). "Phylum-wide analysis of SSU rDNA reveals deep phylogenetic relationships among nematodes and accelerated evolution toward crown Clades". Mol Biol Evol. 23 (9): 1792–1800. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl044. PMID 16790472.

- ^ a b Khadka, Bijendra; Chatterjee, Tonuka; Gupta, Bhagwati P.; Gupta, Radhey S. (2019-09-24). "Genomic Analyses Place Novel Molecular Signatures Specific for the Caenorhabditis and other Nematode Taxa Providing Novel Means for Genetic and Biochemical Studies". Genes. ten (10): 739. doi:10.3390/genes10100739. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC6826867. PMID 31554175.

- ^ "959 Nematode Genomes – NematodeGenomes". Nematodes.org. 11 Nov 2011. Archived from the original on 5 Baronial 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Liu GH, Shao R, Li JY, Zhou DH, Li H, Zhu XQ (2013). "The complete mitochondrial genomes of iii parasitic nematodes of birds: a unique factor order and insights into nematode phylogeny". BMC Genomics. 14 (one): 414. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-414. PMC3693896. PMID 23800363.

- ^ Hodda, M. (2022). "Phylum Nematoda: a nomenclature, catalogue and index of valid genera, with a census of valid species". Zootaxa. 5114 (1): 1–289. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5114.i.1.

- ^ a b Nyle C. Brady & Ray R. Weil (2009). Elements of the Nature and Properties of Soils (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN9780135014332.

- ^ Ruppert EE, Trick RS, Barnes RD (2004). Invertebrate Zoology: A Functional Evolutionary Approach (7th ed.). Belmont, California: Brooks/Cole. ISBN978-0-03-025982-one.

- ^ Weischer B, Brown DJ (2000). An Introduction to Nematodes: General Nematology. Sofia, Republic of bulgaria: Pensoft. pp. 75–76. ISBN978-954-642-087-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 50 thousand Barnes RG (1980). Invertebrate zoology. Philadelphia: Sanders College. ISBN978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ "The sensory cilia of Caenorhabditis elegans". www.wormbook.org.

- ^ Kavlie, RG; Kernan, MJ; Eberl, DF (May 2010). "Hearing in Drosophila requires TilB, a conserved protein associated with ciliary motility". Genetics. 185 (1): 177–88. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.114009. PMC2870953. PMID 20215474.

- ^ Lalošević, Five.; Lalošević, D.; Capo, I.; Simin, 5.; Galfi, A.; Traversa, D. (2013). "High infection charge per unit of zoonotic Eucoleus aerophilus infection in foxes from Serbia". Parasite. xx: three. doi:ten.1051/parasite/2012003. PMC3718516. PMID 23340229.

- ^ Bell 1000 (1982). The masterpiece of nature: the evolution and genetics of sexuality. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN978-0-520-04583-v.

- ^ a b Johnigk SA, Ehlers RU (1999). "Endotokia matricida in hermaphrodites of Heterorhabditis spp. and the event of the food supply". Nematology. 1 (7–8): 717–726. doi:10.1163/156854199508748. ISSN 1388-5545.

- ^ Haag ES, Helder J, Mooijman PJ, Yin D, Hu South (2018). "The Development of Uniparental Reproduction in Rhabditina Nematodes: Phylogenetic Patterns, Developmental Causes, and Surprising Consequences". In Leonard, J.50. (ed.). Transitions Between Sexual Systems. Springer. pp. 99–122. doi:ten.1007/978-3-319-94139-4_4. ISBN978-three-319-94137-0.

- ^ Yanoviak SP, Kaspari M, Dudley R, Poinar G (April 2008). "Parasite-induced fruit mimicry in a tropical canopy ant". Am. Nat. 171 (4): 536–44. doi:10.1086/528968. PMID 18279076. S2CID 23857167.

- ^ Batra, Suzanne W. T. (1965-ten-01). "Organisms associated with Lasioglossum zephyrum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae)". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 38 (iv): 367–389. JSTOR 25083474.

- ^ Purcell M, Johnson MW, Lebeck LM, Hara AH (1992). "Biological Command of Helicoverpa zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) with Steinernema carpocapsae (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) in Corn Used as a Trap Ingather". Environmental Entomology. 21 (half-dozen): 1441–1447. doi:10.1093/ee/21.6.1441.

- ^ Smiley RW, Dababat AA, Iqbal Southward, Jones MG, Maafi ZT, Peng D, Subbotin SA, Waeyenberge L (2017). "Cereal Cyst Nematodes: A Circuitous and Destructive Group of Heterodera Species". Establish Disease. American Phytopathological Social club. 101 (10): 1692–1720. doi:x.1094/pdis-03-17-0355-fe. ISSN 0191-2917. PMID 30676930.

- ^ Kloosterman, Stephen (April 2022). "Small Soldiers". Light-green House Production News. Vol. 32, no. four. pp. 26–29.

- ^ Riotte L (1975). Secrets of companion planting for successful gardening. p. 7.

- ^ U.s. awarding 2008072494, Stoner RJ, Linden JC, "Micronutrient elicitor for treating nematodes in field crops", published 2008-03-27

- ^ Loothfar R, Tony South (22 March 2005). "Suppression of root knot nematode (Meloidogyne javanica) after incorporation of Indian mustard cv. Nemfix as green manure and seed meal in vineyards". Australasian Establish Pathology. 34 (1): 77–83. doi:ten.1071/AP04081. S2CID 24299033. Retrieved fourteen June 2010.

- ^ Warshafsky, Z. T., Tuckey, T. D., Vogelbein, W. K., Latour, R. J., & Wargo, A. R. (2019). Temporal, spatial, and biological variation of nematode epidemiology in American eels. Canadian Periodical of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 76(10), 1808–1818. https://doi.org/x.1139/cjfas-2018-0136

- ^ Jithendran, & Bhat, T. . (1999). Epidemiology of Parasitoses in Dairy Animals in the Northward W Humid Himalayan Region of Republic of india with Particular Reference to Gastrointestinal Nematodes. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 31(4), 205–214. https://doi.org/ten.1023/A:1005263009921

- ^ Morgan, & van Dijk, J. (2012). Climate and the epidemiology of gastrointestinal nematode infections of sheep in Europe. Veterinary Parasitology, 189(i), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.03.028

- ^ Nosowitz, Fan (2021-02-08). "How California Crops Fought Off a Pest Without Using Pesticide". Mod Farmer . Retrieved 2021-02-fifteen .

- ^ Pramer C (1964). "Nematode-trapping fungi". Science. 144 (3617): 382–388. Bibcode:1964Sci...144..382P. doi:10.1126/science.144.3617.382. PMID 14169325.

- ^ Hauser JT (December 1985). "Nematode-trapping fungi" (PDF). Cannibal Institute Newsletter. xiv (1): 8–eleven.

- ^ Ahrén D, Ursing BM, Tunlid A (1998). "Phylogeny of nematode-trapping fungi based on 18S rDNA sequences". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 158 (2): 179–184. doi:10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00519-three. PMID 9465391.

- ^ "Columbia Survivors". Astrobiology Magazine. Jan ane, 2006. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ Szewczyk, Nathaniel J.; Mancinelli, Rocco L.; McLamb, William; Reed, David; Blumberg, Baruch S.; Conley, Catharine A. (December 2005). "Caenorhabditis elegans Survives Atmospheric Breakup of STS–107, Space Shuttle Columbia". Astrobiology. v (6): 690–705. Bibcode:2005AsBio...5..690S. doi:10.1089/ast.2005.v.690. PMID 16379525.

- ^ Raymond, Mélianie R.; Wharton, David A. (Feb 2013). "The ability of the Antarctic nematode Panagrolaimus davidi to survive intracellular freezing is dependent upon nutritional condition". Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 183 (2): 181–188. doi:x.1007/s00360-012-0697-0. ISSN 0174-1578. PMID 22836298. S2CID 17294698.

Further reading [edit]

- Atkinson, H.J. (1973). "The respiratory physiology of the marine nematodes Enoplus brevis (Bastian) and E. communis (Bastian): I. The influence of oxygen tension and body size" (PDF). J. Exp. Biol. 59 (1): 255–266. doi:10.1242/jeb.59.1.255.

- "Worms survived Columbia disaster". BBC News. 1 May 2003. Retrieved four November 2008.

- Gubanov, Northward.M. (1951). "Behemothic nematoda from the placenta of Cetacea; Placentonema gigantissima nov. gen., nov. sp". Proc. USSR Acad. Sci. 77 (6): 1123–1125. [in Russian].

- Kaya, Harry K.; et al. (1993). "An Overview of Insect-Parasitic and Entomopathogenic Nematodes". In Bedding, R.A. (ed.). Nematodes and the Biological Control of Insect Pests. Csiro Publishing. ISBN9780643105911.

- "Giant kidney worm infection in mink and dogs". Merck Veterinary Manual (MVM). 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S (August 1976). "The construction of the ventral nerve string of Caenorhabditis elegans". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 275 (938): 327–348. Bibcode:1976RSPTB.275..327W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1976.0086. PMID 8806.

- Lee, Donald L, ed. (2010). The biological science of nematodes. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN978-0415272117 . Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- De Ley P, Blaxter One thousand (2004). "A new arrangement for Nematoda: combining morphological characters with molecular trees, and translating clades into ranks and taxa". In R Melt, DJ Hunt (eds.). Nematology Monographs and Perspectives. Vol. 2. Eastward.J. Brill, Leiden. pp. 633–653.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nematoda. |

- Harper Adams University College Nematology Research

- Nematodes/roundworms of man

- http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/phyla/ecdysozoa/nematoda.html

- European Social club of Nematologists

- Nematode.internet: Repository of parasitic nematode sequences.

- http://webarchive.loc.gov/all/20020914155908/http://www.nematodes.org/

- NeMys World gratuitous-living Marine Nematodes database

- Nematode Virtual Library

- International Federation of Nematology Societies

- Social club of Nematologists

- Australasian Clan of Nematologists

- Research on nematodes and longevity

- Nematode on BBC

- Nematode worms in an aquarium

- Phylum Nematoda – nematodes on the UF / *IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nematode

Posted by: davenportfortalwyneho.blogspot.com

0 Response to "4. What Are The Main Characteristics Of Animals That Belong To The Phylum Nematoda?"

Post a Comment